It’s election time in Indonesia. Candidates face the daunting challenge of introducing themselves to over 193 million voters. Across thousands of different islands. Stretched over 3 timezones. From big, bustling cities to remote jungle villages.

Incumbent president Joko Widodo has decided to share the story of his life on social media¹. He tells of a day when bulldozers came roaring. His home. His father’s carpentry business. The friendly neighbourhood. All ripped apart into a desolate field of rubble and debris to make way for public facilities. From one day to the next, young Joko Widodo and his family were left out on the streets scouring for shelter and a new way – any way – to make some money. Nothing left but a few belongings rescued from the chaos.

We all have those moments in our lives. Moments when life as we know it simply ceases to exist. Perhaps you’re confronted with a debilitating illness that affects every aspect of your being. Or your partner leaving you for someone else after 16 years of marriage. Perhaps you’ve been laid off from the only job you’ve ever known how to do.

But you can also find yourself derailed by things you actually wanted to happen. Like finding that the city you so enthusiastically decided to move to is actually an awful place to live. Or the birth of your twins having a far more abrupt and fundamental impact on your life than you ever expected.

In life-changing conditions like these, discovering what you want takes place under very stressful circumstances. This month’s Insight focuses on what to look out for as you juggle with the many different things happening at the same time.

1. Facing a mix of taxing priorities²

All you know is that you’ve somehow ended up in a situation you don’t want to be in. Every cell in your body screams that it isn’t right. But there’s nothing you can do about it. There’s no “Undo” button. There are no re-runs. Your old life. Your old self. Dreams, hopes and expectations. You’re not sure where they went or if you can ever get hold of them again.

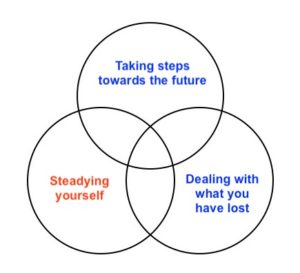

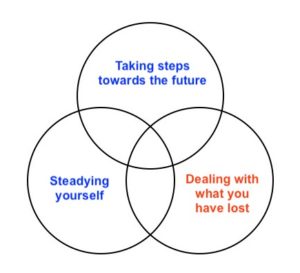

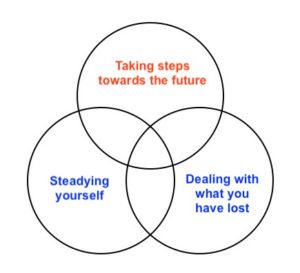

Somehow, you have to figure out how to deal with the disruption. Your time and energy torn between different demands and priorities. Getting overwhelmed doing one thing and not getting round to another is all too real. The challenge is to find a way to:

a. Steady yourself

b. Deal with what you have lost

c. Take steps towards the future

a. Steadying yourself

As you reel from life thundering right over you, you need to find some balance. Some solid ground or something to latch onto. Steadying yourself is all about making sure that you get through this as well as you possibly could. Things are challenging enough as it is.

As you reel from life thundering right over you, you need to find some balance. Some solid ground or something to latch onto. Steadying yourself is all about making sure that you get through this as well as you possibly could. Things are challenging enough as it is.

1. Secure fundamental resources:

- If you lack resources to fulfil basic, immediate needs like food, water, shelter, heat (if it’s cold), clothes, cover, safety or security, take care of those first.

- If relevant, secure a source of income for the short and mid term.

2. Get help from people around you:

- Foster supportive relationships with people who can help you with practical matters or who can provide a shoulder to cry on.

- Ask for help. Note that others may not know what you need or may feel insecure about how to act. Help them to help you, if necessary.

3. Take care of yourself:

- Eat and drink regularly and healthily.

- Keep your body fit by doing some kind of physical activity.

- Recharge regularly. If getting a good night’s sleep is difficult because thoughts and emotions are keeping you up at night, at least try to rest every now and again.

- Continue to take care of your personal hygiene and appearance.

4. Steady your day:

- Find routines that help you build some structure in your day, like getting up in the morning at a consistent time or with the same morning ritual.

- If you had healthy habits that still fit in the current situation, keep doing them.

- Try to stay clear of any habits that are likely to have a bad effect on your wellbeing. No matter how painful, try not to numb your feelings by using alcohol or drugs.

You may find that your heart is not necessarily in any of this. That you’re just going through the motions, as if these were all dull, humdrum tasks. Doesn’t matter. It’s part of the emotional rollercoaster to feel this way. Don’t worry about having a bad day. Give yourself a hug and keep on going. Try to see every action as something you do to be kind to yourself in these times of turmoil.

b. Dealing with what you’ve lost

Whenever your life changes like this, you lose something. That “something” can take many different forms. The presence of a loved one. The freedom to go anyplace anytime. A steady income. Your trust in a friend. Parts of your identity …

Whenever your life changes like this, you lose something. That “something” can take many different forms. The presence of a loved one. The freedom to go anyplace anytime. A steady income. Your trust in a friend. Parts of your identity …

In the early stages of a change, steadying yourself and managing the immediate impact may take all of your effort and strength. But as you begin to realise what you’ve lost, a process of mourning starts which may bring about all kinds of different emotions. Like shock, anger, sadness and desperation, but also sympathy, joy and hope. You may go back and forth between them or feel them all at the same time. Contrary to what some experts originally thought there is no universal, linear process that constitutes “good” mourning. You might go from anger to sadness to gratitude for what once was, then back to anger and into desperation. This is normal, so don’t worry about it when your grief surfaces in different, sometimes recurring forms over time.

1. Factors in the loss experience

What it means to mourn is very personal and happens in the context of a certain time and place. Different factors play a role in how you might experience a loss.

-

- The kind of loss

Some types of loss can be clearly defined and are relatively common. Like a loved one dying of old age. Depending on time and place, such losses are usually surrounded by a range of rituals and ceremonies. Think of a funeral, or a gathering 100 days after someone has passed to mark a transition for both the dead and the living, or an annual remembrance. As a bereaved person, you become part of a social process and structure that supports you in your mourning.

Other types of loss are more ambiguous, difficult to define or less common. While people still sympathise with your loss, there are no broadly shared rituals, processes or structures in place to support you in your grief. For example, when a loved one goes missing and it remains unclear what happened to him/her and whether or not s/he is still alive.

And then there are the types of loss that carry a social stigma, making it hard for those affected to secure any kind of support. Such as giving birth to a disabled child in a country where disability is seen as an ominous sign. Or receiving an HIV diagnosis in a place where people are ill informed about HIV/AIDS.

-

- The actual impact of the loss

A loss generally has an immediate impact on your daily life, but it may also generate additional losses. For example, if you’ve gone bankrupt, you may have to move to a cheaper location, which in turn may bring about changes in the relationship with your spouse or your opportunities for the future.

-

- Your perceptions and beliefs around a loss

Apart from the type of loss and its actual impact, what you think and feel makes a big difference in how you experience and deal with it. The same event can leave one person in complete despair, while another feels confident he’ll get through it. There’s no right or wrong here. It’s just what it is at that given time.

-

- The resources you have to cope with a loss

Of course, a lack of resources will make it more difficult to deal with a loss. Sometimes, the challenge is to become aware of resources that are there, but that you are not yet drawing on.

2. Why mourn?

Experiencing a life-changing loss is not easy. It takes a toll on you emotionally, cognitively and physically no matter what.

Experiencing a life-changing loss is not easy. It takes a toll on you emotionally, cognitively and physically no matter what.

Sometimes mourning is delayed, as your own mental defence mechanisms kick in and shield you from grief that is too overwhelming to handle at that time. Sometimes you don’t get the chance to mourn what you have lost as you barely manage to keep going. And sometimes you just disengage from the process, because you don’t want to feel the grief anymore.

Unfortunately, research has shown that unresolved grief can become an important contributor to mental health issues such as depression and anxiety disorders, behavioural problems and family conflicts. And the problem with unresolved grief is that it has a way of catching up with you, sometimes popping up years later at a moment when you least expect it.

So mourn what you’ve lost when you have a chance to do so. Try to think of grief as a natural response to loss. Something you need to go through to heal. A bit like your body becoming temporarily ill while it’s busy overcoming a virus.

3. Some guidance

Mourning is such a personal and context-dependent experience, that there’s no standard recipe that applies to everyone everywhere. But research on mourning does provide some guidance that may be helpful.

-

- Define what you have lost

Being aware of what you’ve lost supports the grieving process. Try to be specific. What have you lost exactly? For instance, if you have lost your job, don’t just say “I lost my job”, but try to define what it means to you. For example, “I lost a reason to get up in the morning.” Or “I lost something I was proud of.” Or “I lost my only source of income.”

-

- Become aware of how you feel

Get in touch with your thoughts, emotions and beliefs around each of these components of your loss. Try to observe what’s going on inside you without judgment or censorship. A method that has proven particularly helpful in this regard is writing: to capture everything you’re experiencing in words and let go of them on paper.

-

- Review your options in coping and available resources

What are you already doing to cope? What resources do you have inside and around you? Your own skills and experience, people who can help, possible funds et cetera. Which resources are you already using, which ones could you possibly still leverage?

-

- Mark transitions

To mark transitions in the grieving process, often in a symbolical way, has proven to support healing. If the loss you’re going through is not accompanied by rituals or ceremonies that are broadly shared in your community, try to come up with your own. Like dedicating a prayer or poem to someone at a certain point in time, or having a special gathering with others to mark a next phase of change. Some people also find great comfort in remembering what was special or significant and giving it a place in their new lives. Such a picture or a symbol they keep close.

-

- Forgive

Blame and guilt tend to interfere with the grieving process. If you blame anyone for what happened, could you find a way to forgive that person (including yourself)?

-

- Your story

Narrative therapy has shown that developing and sharing meaningful stories supports mourning and healing. What is the story of your loss? If you feel comfortable sharing it with others, tell them your story. Listen to the stories of others who are affected and appreciate what it has meant to them (remember that everyone deals with loss differently).

Give yourself time to experience your loss at your own pace. Be patient with yourself. Feelings of grief may wax and wane. That’s normal, so don’t worry about it. In time, ideally, you get to a place where you find acceptance and look back at what happened in peace.

c. Taking steps towards the future

Apart from steadying yourself and dealing with what you’ve lost, you’ll need to figure out what direction to take.

Apart from steadying yourself and dealing with what you’ve lost, you’ll need to figure out what direction to take.

Considering what you want next may not come easy. As you juggle all the different demands and priorities, it may take some time before you find a moment to really think things through.

In addition, your new reality may be so unfamiliar or uncertain, that you’re forced to make decisions based on very little information and with limited understanding of consequences.

Also, you may find it difficult to make decisions about the future, when you’re not yet ready to let go of (parts of) your past life. For instance, when your spouse develops Alzheimer’s disease and is still physically present, but psychologically no longer there as the person you once knew.

As you move forward, just take one step at the time at a pace that feels comfortable for you. Be patient with yourself and those around you. Remember that everyone responds in his/her own way.

If you’re unsure how to proceed and need some ideas, perhaps the following articles can help:

- Small and simple things to start with today: Illustrating how you can start with little things that are part of your daily life in working towards a new future.

- Burning through the fog in your mind: Showing you a specific writing technique to help you make sense of everything you are thinking and feeling, and discover what you want.

- What to do when there’s too much to learn: Providing tips on how to develop skills, knowledge and abilities that are new to you.

Footnotes:

1. Cerita Hidup Jokowi by Kratoon, April 2019.

Here’s the full 9-minute animation video about the life of Indonesia’s incumbent president Joko Widodo.

For subtitles in English (or other languages), simply click on the CC sign. The original YouTube link is https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RNqYSNv8zy4.

2. Some key resources for this month’s Insight:

- Almeida, D.M., & Wong, J.D. (2009). Life transitions and daily stress processes. In: Elder, G.H., & Giele, J.Z. (Eds.), The Craft of Life Course Research (pp. 141–162). New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press.

- Aspinswall, L.G. (2004). Dealing with adversity: Self-regulation, coping, adaptation, and health. In: Brewer, M.B., & Hewstone, M. (Eds.), Perspectives on Social Psychology. Applied Social Psychology (pp. 3–27). Malden, MA, USA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Becker, G., & Becker, G. (1999). Disrupted Lives: How People Create Meaning in a Chaotic World. Oakland, CA, USA: University of California.

- Betz, G., & Thorngren, J.M. (2006). Ambiguous loss and the family grieving process. The Family Journal: Counseling and therapy for couples and families, 14(4), 359-365.