A common reason why people aren’t sure what they want, is feeling overwhelmed by the prospect of having to learn something that feels so far beyond their current life that it seems unattainable.

Technically speaking, in such cases, it’s not entirely true that someone doesn’t know what they want. They do know. Or they have a vague notion of what it might be. But it just doesn’t feel like a real option.

If this is you, don’t despair! Yes, it’s true that learning something completely new will take time and effort. And yes, it’s true that when you happen to be a bit older, you may not learn as easily as before. And fair enough, you’re not very likely to become the next world champion sprinting, if you’re 56 years of age and have never done any sports in your life.

But within the restrictions of your personal blueprint, your brain can help you learn just about everything and it keeps this ability until well into old age¹·². So don’t give up on yourself just yet!

Here’s what you do …

1. Understand how it works

First, you need to understand how it works, so that you know what will be effective and what not.

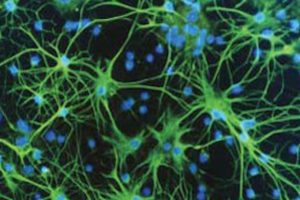

The core part of your body that allows you to learn is your brain. It’s made up of millions of brain cells, called neurons, that act as communication centres. They send electrochemical signals to other cells across different parts of your brain, forming so-called neural pathways. If this sounds puzzling, have a quick look at the article “Meet your biggest ally: Your brain“.

Now, to put it very simple, when you learn something new – like new skills or information or when you try to change your emotional response to certain circumstances – your brain actually physically changes.

While you are practicing something new, different neurons get triggered than usual. Over time, the connections between them change shape. The neural networks that are now more intensively used become denser and more active, enabling you to get better and better at what you’re trying to do.

To make all this happen, your body extracts the necessary building blocks from the peanut butter sandwich and the fried rice with seafood and mango smoothie you had today. These building blocks are then transported to the locations in your brain where adjustments are needed.

Research shows that the brains of people who regularly learn something new and do things that engage different parts of the brain, have more diverse and interconnected neural pathways. This actually helps the brain in maintaining its ability to adapt. A bit like regular exercise helps your body to stay fit. So from a brain-health point of view, continuing to learn is a good thing in and of itself.

Note that neural pathways that are used less, will become lighter over time. This is the brain’s way to keep energy consumption as efficient as possible, which – over the course of evolution – has been important for survival in situations of food scarcity (the brain takes up around 20% of the body’s daily energy consumption in resting state). Don’t worry though. You can always re-activate such neural pathways (which, I guess, is bad news, if it concerns unwanted habits you’ve picked up along the way).

Have a look at the next short video by Sentis that explains this concept of your brain’s adaptability – often referred to as “neuroplasticity” – in a very effective way. If you find subtitles helpful, just turn on “Captions” under the “CC” sign in the bottom of your screen.

Now, learning new things does take a little bit more effort as we get older, because general brain performance declines over time due to changes in for instance blood flow to the brain, cell structure and cell functioning. It’s difficult to say just at what rate, as our genetic make-up and lifestyle each have a big impact. But most of us start noticing that it’s becoming a bit more challenging, once we’re over 30.

However, our brain keeps its ability to change and adapt until we’re very, very old¹. And you can even optimize its potential further by maintaining a healthy lifestyle and keeping your brain active (see “Meet your biggest ally: Your brain” for more tips on how to keep your brain fit and agile).

2. Understand how it feels

Apart from understanding how it works, it helps to understand what it may feel like along the way, so you won’t be caught off guard.

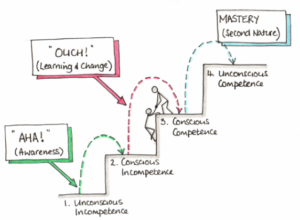

Assuming that you’re trying to master something that is completely new and that requires more than just a few simple skills, you’re likely to experience the following phases².

Assuming that you’re trying to master something that is completely new and that requires more than just a few simple skills, you’re likely to experience the following phases².

- Unconsciously incompetent

- Consciously incompetent

- Consciously competent

- Unconsciously competent

Each indicates a different level of mastery and each has its own challenges in terms of the learning process as well as the emotions you go through. Let’s take a closer look at each of those levels.

a. Unconsciously incompetent

In the beginning, you simply “don’t know what you don’t know”. You are blissfully unaware of what it takes to master the required competences. You may even think it will be easy.

I remember a friend who said “How hard can it be, really?” upon deciding to open her own restaurant. She remembered all those times she’d sat in restaurants, annoyed with their service and seeing all kinds of possibilities to improve performance. She couldn’t wait to get started …

This phase is usually not very emotionally challenging, although you may feel a bit anxious about the unknown that lies ahead.

B. Consciously incompetent

Once you start trying, you become aware of things you do not know or are unable to do. This is a phase filled with trial and error; trying, failing, trying again, succeeding somewhat, trying again et cetera.

For my friend, the new restaurant owner, this phase came with the realisation that she didn’t know how find the right staff and get them to give customers exactly the kind of service she wanted. She also realised she didn’t really know how to use social media to get her new restaurant more well-known. Customer numbers remained very low.

Emotionally, this can be a very challenging phase. Many of us do not enjoy this feeling of not knowing our way. We may feel inadequate or ashamed when we fail or make mistakes. Or frustrated when we go one step forward only to take two steps back.

But hang in there! It’s all part of the process. Have a good cry every now and again. Forgive yourself for the mistakes you make. Find out how you can improve. Get some support from family or friends. Celebrate your successes, however small.

And remember: every time you try, your brain will, again, adjust a little bit more. You just have to keep on trying.

C. Consciously competent

Things get easier at the next level, when your brain has managed to adjust to a level that allows you to be successful as long as you pay attention. You cannot yet go “on automatic pilot” and you do not yet get it right every time, but as long as you stay focused, you broadly manage to do what you intended to do.

In this phase, my friend, the restaurant owner, used to consciously reflect at the end of each week on what she had done well the week before and what she needed to do differently the next week to get her team to offer great service and give the restaurant more exposure. Customers numbers were up and people who had eaten at the restaurant were happy. All in all, she started doing much better.

D. Unconsciously competent

In the last phase, you’ve mastered the new ability to such a level that you no longer have to think about it.

Being unconsciously competent is an interesting phase. One we tend to regard very favourably, because we have fully mastered something. However, we often don’t realise there are two important pitfalls. First, because you’re no longer aware of how you do things and how you tie different elements together, it may actually be rather difficult to change if change is still needed. Secondly, when you’ve been at this level for a while, you do things without much conscious thought. This also means that you may find it rather difficult to explain how you do things. This can pose a considerable challenge if there are people who want or need to learn from you. But let’s not linger here too long as this is something for future concern …

3. And now … just start … however small

Time will pass, whether you try to learn something new or not. And learning new things in itself helps to keep your brain healthy and adaptable. So you might as well just start, however small, and see where it takes you .

a. Create opportunities for learning

What you’re trying to learn is often made up of different elements. If it’s not possible to learn everything all at once, try to figure out how you could develop relevant skills or knowledge in steps.

As an example, let’s say you have this dream of one day opening a restaurant, like my friend. You currently have a regular office job with three kids at home and can barely make ends meet. There’s no way for you to quit everything now to go back to school full-time. You’re not even sure you’ll ever be able to get the right diplomas or secure the money to start a restaurant. But all this doesn’t mean there’s nothing you can do.

The easiest way is to find things to learn that fit into your current life. If you cook, try out recipes for foods that you may want to serve and develop a list of favourites. Talk to friends and family about their restaurant experiences and see how that matches with your own ideas about customer service. Explore how they find new restaurants to visit. Ask a restaurant owner if s/he would be willing to share experiences with you on what it’s like to open a restaurant. Find information on the Internet on what it takes to run a business in a financially healthy and realistic way. Do volunteer work at something like a local shelter or charity kitchen to take in the experience. Et cetera et cetera. Whatever works for you. Get creative. Have some fun …

The point is that there are always relevant things you can learn. You may not be able to open that restaurant for many years to come, but you’re getting yourself ready for such a possibility in the future. And you’re gaining new competences and keeping your brain fit along the way …

If you’re looking for some further inspiration, have a look at the article “Small and simple things to start with today“. It wasn’t written for this purpose, but it might help you get some creative ideas.

b. Small steps can go a long way …

As in the restaurant example, you may not have a lot of time or resources in your current life to learn or do something new. I often meet people who then just give up. Who feel that it’s no use to even try, because they can only take tiny steps.

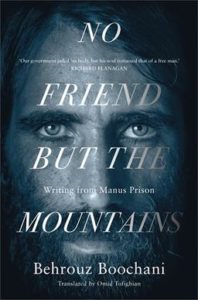

As I’m writing this, I’m watching a news item about a Kurdish-Iranian man. His name is Behrouz Boochani and he’s a journalist, human rights defender, poet and film producer. Last year, he managed to publish his very first book “No friend but the mountains”. He wrote it in the sweltering heat and grim surroundings of a detention centre on a desolate Papua New Guinee island, where he is being held since 2013 together with other refugees. They have nothing but the clothes on their backs and a few personal belongings, and lack any security around their futures.

As I’m writing this, I’m watching a news item about a Kurdish-Iranian man. His name is Behrouz Boochani and he’s a journalist, human rights defender, poet and film producer. Last year, he managed to publish his very first book “No friend but the mountains”. He wrote it in the sweltering heat and grim surroundings of a detention centre on a desolate Papua New Guinee island, where he is being held since 2013 together with other refugees. They have nothing but the clothes on their backs and a few personal belongings, and lack any security around their futures.

The book is 374 pages long. He typed it letter by letter … on his mobile phone. Whenever the internet was working, he would send fragments via What’s App to a friend who helped him translate and publish.

Small steps can go a long way …

c. Give your brain a hand

Like Rome, your revamped neural pathways aren’t built in a day. It could take any time from a few days to a few years, depending on how developed certain neural pathways already were (e.g. if you have previous experience or relevant skills) and to what extent they need to change. You cannot force these physical changes, but the good news is that there are things you can do to help the process along.

-

- Practice repeatedly and deliberately, so that neural pathways in your brain are activated optimally and often enough to keep on developing.

- If you have a bad day, just try again the day after. Remember that your brain will keep on adjusting every time you give it another go.

- When you’re learning, try to involve as many of your senses as possible. If there are any opportunities, try and experience something yourself instead of only reading or hearing about it. This will not only make for a full, real-life experience, but it will also help your brain to adjust.

- Support your brain’s construction efforts by making sure that it (1) has the right building blocks and gets enough energy (e.g. eat and drink healthily) and (2) gets every opportunity to make the physical changes that are needed (e.g. get some regular exercise to optimise blood flow to the brain and try to enjoy some good quality sleep).

- In general, keep your brain fit and adaptable by maintaining a healthy lifestyle and regularly challenging it by learning new things. Again, also see “Meet your biggest ally: Your brain“.

Footnotes:

Key sources for this month’s Insight: (1) Biological psychology, James W. Kalat (2014, 11th edition). Course Technology, Cengage Learning EMEA, UK. (2) Human Anatomy & Physiology, Elaine N. Marieb & Katja Hoehn (2016, 10th edition). Pearson, London UK, (3) BrainFacts at www.brainfacts.org, and (4) the Dana Foundation at www.dana.org.

1. Each one of us has been endowed with a specific genetic inheritance, which includes for example our basic body structure and composition, the colour of our eyes, hair and skin, but also our core personality and intelligence. Combined with the impact of critical incidents and the way we went through key development phases during childhood and early adolescence, we each have certain stable features which can both enable as well as restrict our development in a certain direction.

So, no, everyone cannot become anything they want by simply practicing consistently and repeatedly. But within the restrictions of someone’s personal blueprint, the human brain is very much capable of continued adaptation and learning.

2. Assuming that there is no trauma or disease that affects the functioning of the brain.

3. This model was originally developed by Noel Burch in the 1970s for Gordon Training International. The picture is taken from Reddit, but its original source is unknown.